Written by: Kevin Cann

I see this statement a lot on the interwebs, “Technique is not a one size fits all approach. You should lift how you are comfortable and strongest.” There are some truths to that statement, but it is taken much too far from the majority of the population spewing it.

It seems to mostly come from younger and less experienced lifters and coaches who cite research that is performed on even less experienced lifters. In many cases I think it is nothing more than a justification for their own shitty technique, whether subconsciously or consciously driven.

I did not get into powerlifting until my 30s. Before that I participated in sports all of the way up to that point, and I also coached a lot of high school and college athletes, including my time as an intern at Harvard University.

The majority of these athletes could not squat for shit, but a lot of them were extremely athletic and could jump through the roof. They also had the ability to accelerate off of a line very quickly. These actions require a lot of force. Ever see the angles in which they initiate these movements?

For a jump test they will always use a countermovement where the hips go back, and the knees stay slightly bent. The hips, knees, and ankles extend while the athlete reaches up extending his back muscles. This latter part is to reach highest for sure, but ever try to jump without extending your back? You definitely do not jump as high.

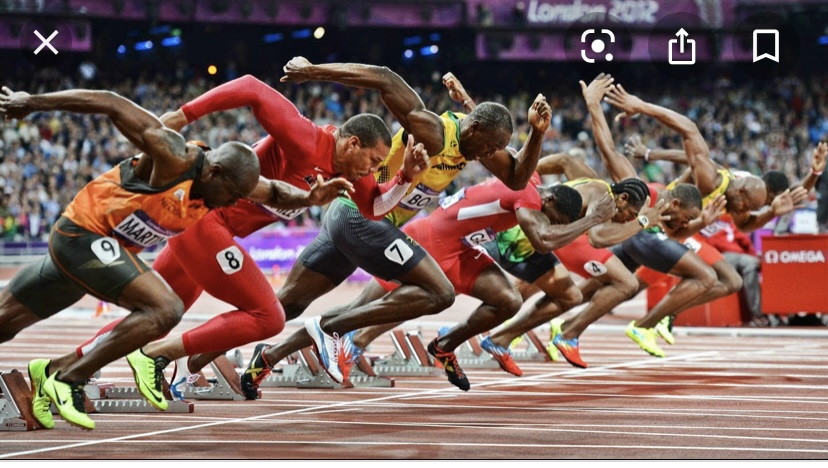

In sprinting, the athlete’s torso remains almost parallel to the ground as they drive the ground away from their bodies with hard hip extension. Look at the picture that I used for this article and look at their shin angles. Notice something? Their shins are all very vertical. Bolt has the most positive shin angle. He quickly corrects this as he gets into his full strides and has some of the most powerful hip extension that you will ever witness anywhere. There are pics of him sprinting in London where he has a much more vertical shin out of the starting blocks.

You might be saying that this has nothing to do with lifting weights. All of these things are related in one way. They are all about producing maximum force. At the end of the day that is all that powerlifting, sprinting, and jumping really are. You might also be saying that sprinting is horizontal forces while squats are more vertical. This is true, but jumping and sprinting have that difference as well, but we see similar mechanics.

Those similar mechanics are with the strong hip extension forces. Under both conditions the athletes attempt to keep their shins as vertical as possible. Why would they want to utilize hip extension in this manner? It is simple, it recruits more and larger muscles. The more muscles, especially larger ones, involved the more force that you can apply to the ground.

This is especially true if we can eccentrically load those muscles and utilize the stretch shortening cycle. Muscles have an elastic component to them that we can utilize to apply more force. Sitting back and opening the knees in the squat eccentrically loads the glutes and hamstrings, but also the adductors which are our strongest hip extensors at depth.

If you squat with your feet inside of your shoulders, this is already a good sign you have weak adductors and glutes or lack the skills to actually eccentrically load them. This is even more true if your knees come in as you squat. Saying “This is the technique that works best for me” is probably not the right attitude to have here. Wouldn’t you want the largest hip extensor with the most leverage to be strong, not hidden? I don’t care how much weight you lift. The goal is to lift a lot more no matter what your numbers are.

When we squat like that, it makes depth more difficult to achieve and actually increases the ROM to hit depth. For every millimeter extra of forward knee travel we get, we need to make it up for it in added strength. So if you squat like this, yes you are very strong, but imagine how strong you would be if you learned to utilize leverages better.

When we sit back and open the knees, we are eccentrically loading the hips, hamstrings, and adductors. When we sit straight down only the quads are eccentrically loaded. We lose a lot of that elastic rebound of the muscles by doing that. We are also not utilizing our biggest and strongest muscles to complete the task.

I am sure some of you are thinking, “Well I lift less that way so I must be different.” That is not true, you just haven’t developed the strength and the skill to best utilize your body. Those athletes I spoke of earlier began participating in sports at a very young age. They had 13-16 years of experience before I saw them. Most powerlifters are very new to the sport and you can find ways to be ok by utilizing your current strengths. This doesn’t mean that there is not a better way to do it.

For one, it does slightly increase injury risk. If you prefer a lot of forward knee travel and you squat 500lbs, this is a good sign you have 500lbs legs, but your low back is capable of handling less. A mis groove where you pitch forward, or a squat you need to put deeper can slightly increase injury risk as tissue tolerance is a thing. Squatting deeper may put the adductors in a position that they are not capable of tolerating as well. As you get stronger you add more volume with these higher weights. If those angles are not addressed, it is a risk factor for some issues.

But don’t you use a Dynamic Systems Theory approach, and doesn’t that theory speak towards movement variability? Yes, I do, and yes it does. This is an extension of the Principle of Dynamic Organization, which states that the body is always looking for a more efficient way to complete the task. The problem is that the body does not always come up with the greatest solutions to the task. If it did everyone that played Little League would be able to throw the ball 90mph. However, that is not the case.

The coach needs to nudge this process to what they deem a more optimal solution. This is where the constraints-led approach comes in. We want to utilize a constraint that limits inefficient strategies and only leaves room to learn more efficient ones.

For example, Sheiko used a wall squat to teach the squat. He had me put my toes up against a wall and squat. This disallowed my knees to travel forward and also forced me to learn to arch my back and lower my hips. It is the only way to execute this drill. Without general technical guidelines to follow, you can’t utilize this approach.

We also use variation in joint angles in training quite a bit. We use box squats a lot which require you to sit back even further than you typically would in a competition style squat. This helps build up the lagging low back and hips and builds explosive strength. We squat with the toes turned out so that the adductors are always emphasized. These positions will be limited by the current strengths in those angles by the lifter. This ensures we are not putting those tissues in positions that they may not be capable of tolerating.

A study was shared to me in IG comments, and my response was requested. IG comments is not the place for that. But let us address this study now.

This study was titled “Inter- and intra- individual variability in the kinematics of the back squat.” This study looked at 10 “competitive” weightlifters that averaged 26 years old. There was an average 1RM of the squat of 363lbs with an average bodyweight of around 200lbs. They all showed differences between themselves and each other in 10 trials at 90% of 1RM.

This was touted to me as the “gold standard” of biomechanical research. Now, I do not disagree with that at all, but we need to understand practical takeaways of this research. This tells me that 10, not very strong weightlifters showed variability in their movements at that given time. The argument then becomes if they move differently there is not one right way to move.

I think this argument is absolutely true in life outside of competitive sports. However, someone can complete a task is most likely fine as long as they do not experience significant pain, or any other issues with it. When we are involved with competitive sports, it loses some of its argument.

Physics matters in sports. If you look at the pic for this article, there are a lot more similarities between the sprinters than differences. A high school track meet would be all over the place. You can get away with certain strategies to squat 300lbs and 400lbs, and even 500lbs. However, as the weights get larger, there tends to be a lot less difference.

I shared my 10 favorite squatters and got poked fun at for choosing larger men, and “mostly’ equipped. For one, most were raw with wraps on, but large men tend to move the most weight. There are far fewer strategies to squat 800lbs plus, than there are to squat 400lbs. Also, get in gear before you tell me it is a different squat. It isn’t that different.

Even those lifters will show variability from rep to rep when analyzed under lab equipment. This is because learning never stops. If you read Supertraining, they even mention this in that text. This is not something new. However, to the coach, the technique is very consistent. They are consistent in how they approach the bar, unrack it, walkout, and execute the lift. There will always be slight differences because no one is perfect, and no one stops learning.

This doesn’t mean we just let people do their own thing to “self-organize.” Your job as a coach is to influence that self-organization to put the lifter into the greatest positions to succeed long term. A technical free for all and you are nothing more than an Excel spreadsheet with an IG account.

I will get “You didn’t cite any articles to prove your point.” No I didn’t, because experience and observation is science in the real world, especially when we observe it through the lens of general principles. I don’t care what people squatting 300-400lbs do. Not one fucking bit. I have multiple girls at far lower bodyweights squatting more than those 200lb men.

This article is almost 1900 words, and I was asked to give my response in IG comments. That is as ridiculous as not sitting back in the squat.