Written by: Kevin Cann

We all know that volume is important to get stronger. Too little volume and progress can stall and even slide backwards. Too much volume and we run the risk of overtraining and injury. So how do we know how much volume is appropriate for each lifter?

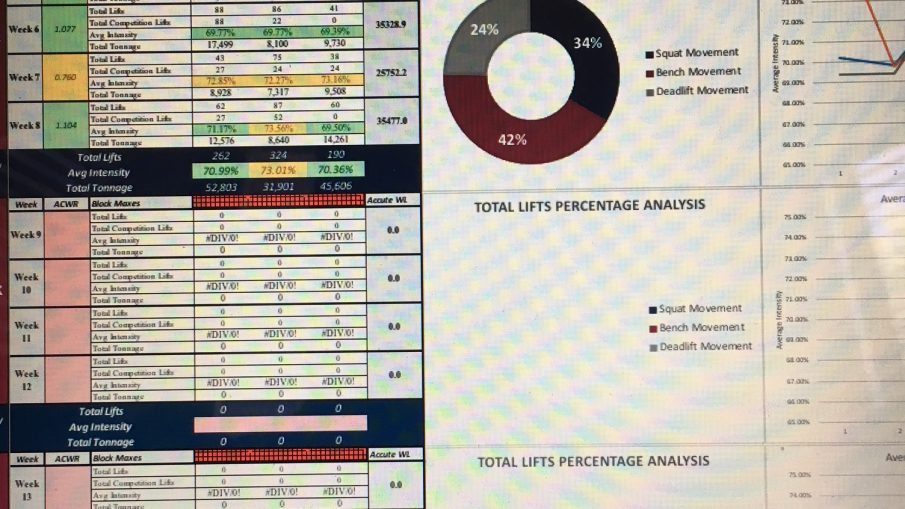

This is where the acute chronic work ratio (ACWR) comes into play. The ACWR analyzes the athlete’s current training and allows the coach to know what the athlete is prepared to handle. This is a pretty popular monitoring tool in field sports, however, I am trying to apply the principles to the sport of powerlifting.

The chronic workload is a 4 week rolling average of the lifter’s total weight lifted. This is the athlete’s baseline volume. This can also be referred to as the athlete’s fitness. We want to stress baseline to push adaptations, hit baseline to maintain, and have some weeks below baseline to allow the athlete to recover.

We do not want to get too far away from baseline at any time due to potential undertraining and also overtraining. However, there may be another reason. Having enough volume in training is actually protective against injury.

Th acute workload is the athlete’s current 7 day training volume. This is the athlete’s fatigue levels. If we divide the chronic workload by the acute workload we get a ratio. A ratio of 1.0 would be baseline. Anything higher is above baseline and anything lower is below baseline.

Most research in team sports shows a sweet spot of .80-1.30 for the ACWR. Some other studies have even narrowed down that range to 1.00-1.20, I believe this was for soccer. My data is closely matched with what the literature has.

With roughly 10 lifters that I applied this too, we saw a range of .90-1.10 for ACWR that led to some really good totals at the last meet. These lifters did have some experience and were qualified for nationals or had qualifying totals in the gym.

The difference between my range and the literature may be due to the internal load measurements. ACWR in the literature weighs external and internal loads. External load is typically gathered by GPS data and may account for distance traveled, accelerations, etc.

Internal load is more subjective. Something like RPE could be utilized here as well as mood questionnaires. I chose to separate external and internal load as the subjective nature of internal load monitoring can throw off my data.

However, RPE has an intention of quantifying a lifter’s effort on a particular set. This information is valuable. What I have decided to do is to use a monitoring system of internal load within the blocks themselves. Basically, using exertion load here.

There will be a constant intensity and rep scheme throughout the block. For example, 80% for 5 sets of 3 reps on the squat. This has to be a competition lift because variations can have beginner gains with the athlete and it makes it difficult to track.

I will compare the athlete’s effort from week to week. We should see technique improve and the sets to begin to look easier. Once they look easier, we will have them take a heavy triple at an RPE 8-9 and use that weight as the new 80%.

During this time I am collecting data on volumes, average intensities, and variations. The ACWR lets me know how much I can push training and still keep the athlete safe. We use this new 80% for a period of time. It should look like there is good effort with some technique breakdown on the 2ndand/or 3rdrepetition.

Again, we monitor this over time. Anything under 80% they use their true 1RM numbers and anything over they just add that change in percentage to the bar. For example, 85% would require them to just add 5% to the bar.

As we were approaching the competition and 90% singles began to come into the program, many of the lifters were hitting all time PRs for fast singles. Programming this way allowed me to do a number of things.

It allowed me to keep progressing training. The ACWR allows me to progress the volume the lifter is training with at a safe rate. It allowed me to identify which variations were working and which ones were not.

I kept variations pretty constant throughout the block as I was monitoring the competition lifts. I choose variations to fix certain technique issues. If the competition lift sets were looking better, it is working, if not it isn’t.

I was also able to identify which volumes and average intensities worked best for each lifter. Some people do better with higher volumes and others do better with more heavy singles. I was even surprised with how much this worked.

ACWR (paired with exertion load monitoring) allows me to monitor the lifter’s readiness for lifting a specific weight for a specific number of repetitions. We have been able to push training far beyond what I would have thought. For example, Kina took a 3×3 with 90% on the deadlift yesterday.

Before, I started utilizing these monitoring tools that would have been 3 sets of 1 at 90% or triples around 80%. We were able to put an extra 10% bar weight over that time period without missing any training days due to injury. Kina was the first one I began using this with back in December. She has put 120lbs on her total since then at a lower bodyweight.

Dave Rocklage has put 110lbs on his total since Raw Nationals, Nick put over 60lbs and climbed into the top 25 of the 93kg class, and Mike Agius put 135lbs on his already national qualifying total at 83kg in 4 months. This was accomplished by missing zero training days due to injury.

They are all currently in a recovery block to allow them to fully recover and to reset all the volume and intensity markers to get ready to hit it again as we approach October. I am excited for the possibilities that this brings to our team and the future of our success.