Written by: Kevin Cann

I am beginning a Strength School with PPS. This is an educational/classroom type thing where we will cover all of the basics in strength training and the theory of PPS. Some do not have access to equipment right now and some have access to very limited pieces of equipment.

It is important that everyone understands the basics of strength training with these limitations. This is how we make good training decisions and get stronger in a minimal environment. Knowledge is power.

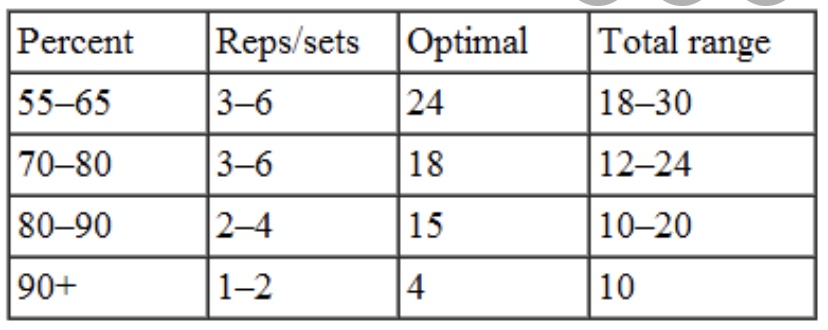

One of the basic pieces we will be covering will be the assignment of volumes and intensities within a given program. Prilepin’s chart is probably the most discussed tool for determining volumes and intensities out there.

As with anything, there are some good features of this chart and also some not so good features of this chart. A.S. Prilepin was a Soviet weightlifting coach. He analyzed the training logs of high level Russian weightlifters.

Upon his analysis he concluded that the rep ranges and number of lifts suggested were optimal for getting better results on the platform. Anything more and the speed of the lifts would decrease, and recovery would become more difficult. Anything less, and the lifter was not getting enough of a stimulus to get stronger.

The Russians had tremendous success in the sport of weightlifting. However, this does not mean that this chart can directly be utilized for powerlifters of all skill levels. We need to keep in mind who was analyzed in this chart.

Elite level Russian weightlifters. These weightlifters started at 8 years old in many cases and have had over a decade of time under the barbell when they were being analyzed. This is not the case for the majority of powerlifters. The longest one of my lifters has been lifting is 5 years.

The lifts themselves are very different. The Olympic lifts require more speed and more technical proficiency than the powerlifts. This does not mean that technique and speed are not important for the powerlifts, but they are called the “slow lifts” for a reason.

The ranges of the chart are quite broad as well. There is a big difference between 70% of 1RM and 80% of 1RM. This chart is just a guideline for the coach to follow. It is not a written in stone dogma that needs to be followed exactly how it is written. There are some good things to take from it.

I actually like the recommendations of the reps per set in Prilepin’s chart, even for powerlifting. I believe that these numbers work best for practicing technical perfection. At the end of the day it may be the total number of reps completed in a training session that matters.

For example, 10 sets of 3 at 65% of 1RM may be more beneficial than 3 sets of 10 at 65% of 1RM. Yes, the intensity of the second example will be more per set, but when we increase the intensity, we often decrease the quality. Both have a place, but the coach needs to understand what they want out of the training day.

I will use 10 sets of 3 at 65% sometimes, but I will also use 5 sets of 5 at 65% and even 5 sets of 6 at 65%. They all have their place. Develop the technical consistency with the 10×3 and challenge it with 5×5 and 5×6.

I am not a huge fan of doing higher rep sets than this as I believe there is diminishing returns with the quality of reps and the physiological demands of the higher rep sets. That is muscular endurance, not muscular strength. The further we get from 1RM, the less specific.

When you look at the chart for powerlifting, I feel we can do higher volumes of the more submaximal weights, but lower volumes of the 90+% weights. I sure as shit could not do 10 singles at greater than 90% of 1RM. I have programmed as much as 40 reps at 70% of 1RM successfully as well.

The fatigue accumulated from the submaximal weights will not breakdown the quality of repetitions in powerlifting quite as easily as it will with weightlifting. Powerlifters will lift heavier absolute loads, making the volumes in the higher intensity zones more difficult to accomplish.

Then we need to take into consideration the variation we use in training. PPS utilizes a lot of variation. Many we know our 1RMs in because we use them in max effort lifts. We do not perform max effort pause squats for example.

Too many lifters will cut the pause short to lift more weight. I bet the Russian lifters would not do that! I found it was best to use pauses as a variation to build technique, but not necessarily absolute strength.

For pauses we will use our best squat for the percentage work. So how does this apply to the chart? A 70% squat with a 2 second pause is much more difficult than a 70% competition squat. However, the chart has a range between 70% and 80%. In this case the numbers of the chart may actually be ok.

However, I would not be doing a 6×4 2 sec pause squat at 80% of 1RM unless the lifter has made some outstanding progress and their 1RM has gone up without us testing it. I do not even prescribe that much volume at 80% with a competition squat. Maybe a 4×4, but usually I will stick with 2-3 reps at that percentage.

In these cases the coach needs to be aware of the increase in intensity in which the variation creates and adjust accordingly. If I am going to pause at 80% of 1RM, I am probably doing 1-2 reps per set and 3 to 5 sets as this would be a very hard training day.

I think too often coaches and lifters are worried about writing the perfect program. The perfect program does not exist. The coach just needs to start somewhere and pay attention. Prilepin’s chart is a fine starting point for any powerlifter.

From there pay attention to how training is progressing. Adjustments will always need to be made. How does their technique look? How is their recovery? What is the intensity of these rep ranges at these percentages for this lifter? If I increase the percentages, now what does their technique and recovery look like? This goes on forever.

Over time from paying attention, you begin to develop your own charts for what works with each lifter. I think generally speaking the volumes and intensities apply to almost everyone with the way that we do things. The difference more comes about with a specific variation and longer term recovery strategies.

Some lifters will struggle more with a particular variation than others. Some lifters need more breaks from the higher intensity efforts than others. But in terms of the number of reps per set and how many sets to perform, they remain very constant from lifter to lifter.

There are generalities that apply to everyone. Prilepin’s chart is based off of these generalities for the weightlifters that were analyzed. From these generalities is where coaching needs to happen to make the necessary adjustments to get the desired training effects for each individual.